Building Bokaka (part 2)

In the last post, I talked about why I’m building Bokaka. This time, let’s get into the how - choosing the right hardware, writing firmware from scratch, and the painful journey of getting two cards to actually talk to each other.

Choosing the MCU

The first decision was picking the right microcontroller. I had a few hard requirements:

- USB support - Bokaka cards need to plug into a computer for syncing with NEXI, so native USB was non-negotiable

- Built-in unique ID - STM32 chips have a factory-burned unique 96-bit ID, which is perfect for identifying each card without needing external components

- Low power - these cards run on a small battery at concerts, so power efficiency matters

- Fast enough for basic crypto - the USB claiming needs some cryptographic operations, so the MCU can’t be too slow

The STM32L053R8 is chosen for the MCU because it has unique ID and low power modes, most importantly it contains USB support which is crucial for dumping handshake data later with NEXI. It is also quite cheap :)

Getting Started with Nucleo Dev Boards

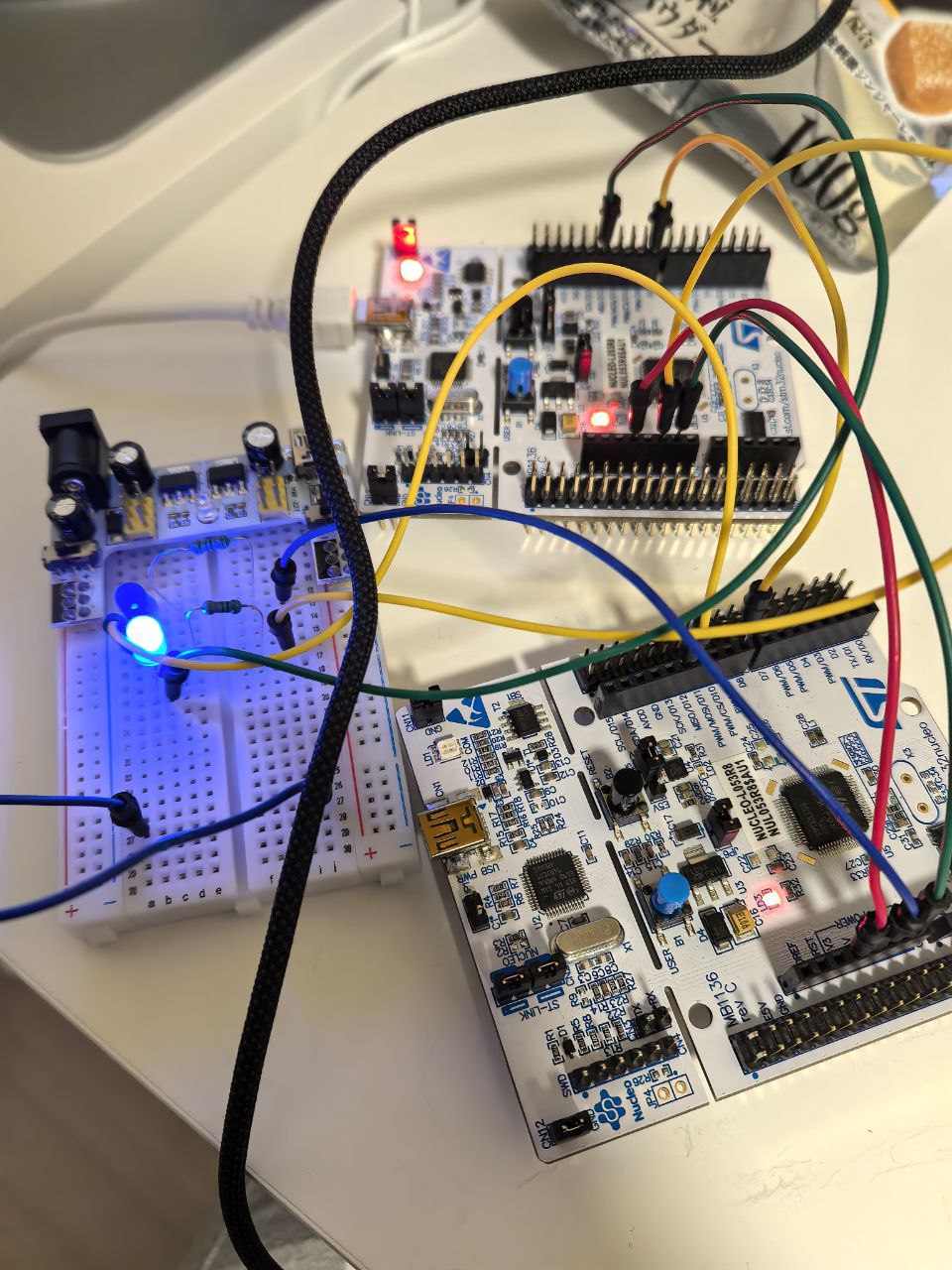

Before designing a custom PCB, I ordered STM32 Nucleo development boards to prototype with. These boards are great because they come with an onboard debugger and break out all the MCU pins for easy experimentation.

The board arrived from China and after some testing I got some quick sketch running with PlatformIO

Writing the Firmware

With the dev board in hand, it was time to start writing firmware. I decided to use PlatformIO with a heavily abstracted layer (HAL), this allows me to quickly test my thoughts and iterate on them without have to worry about pin assignment, STM32CubeIDE. The plat to write the firmware is the following:

- Write a simple USB serial command and response feature that will allow me to send commands to the board

- Adding helpers to retrieve the unique ID from the board and save it in memory for easy access

- Test the encryption capability and speed on the board

- Write the 1-Wire communication protocol implementation

USB Serial Communication

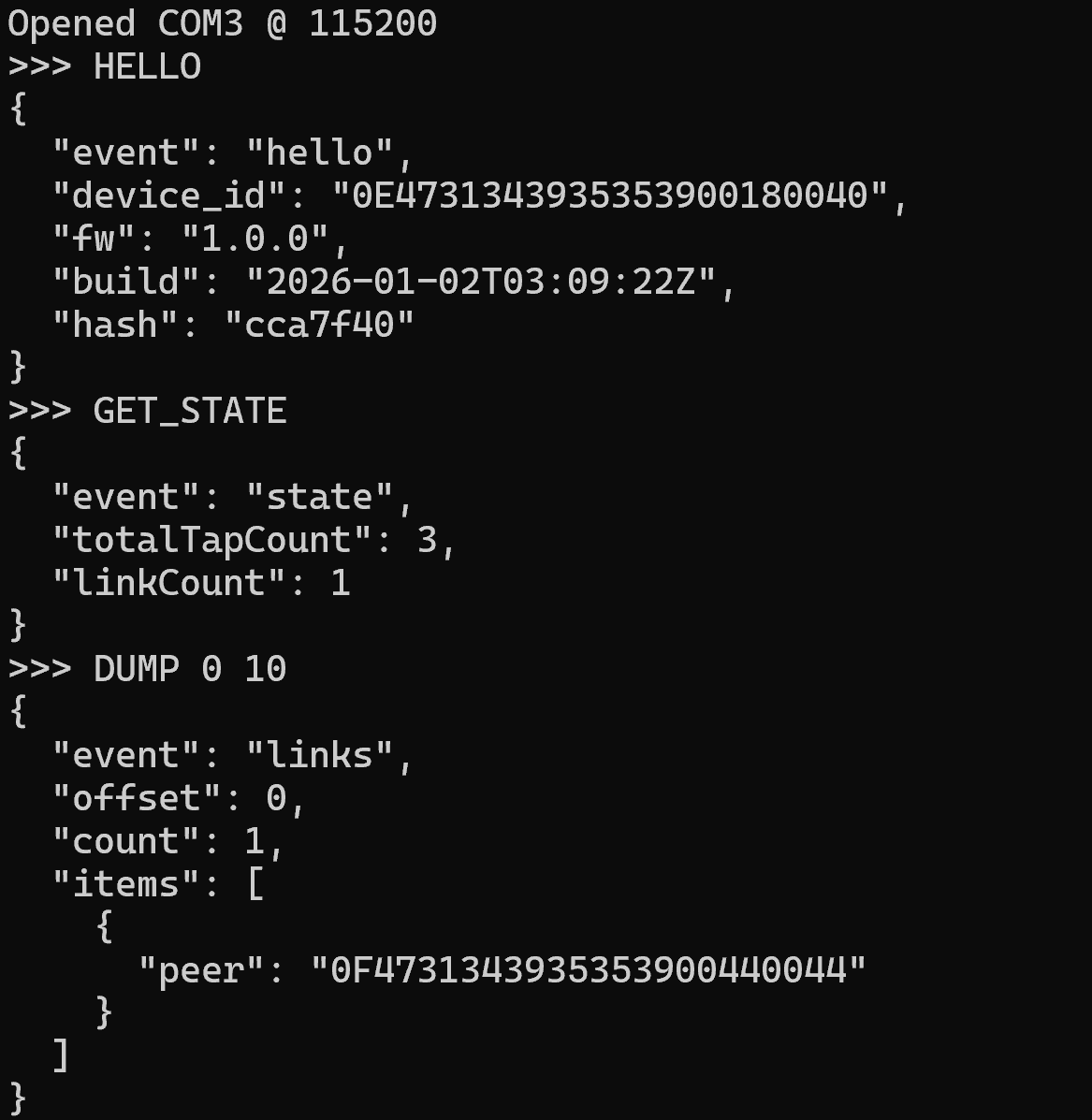

The first milestone was getting USB serial communication working. When you plug a Bokaka card into your computer via USB, it enumerates as a CDC serial device - no drivers needed. This is how users will eventually sync their cards with NEXI.

The command handler sits on top of a layered architecture:

1 | ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ |

Commands are newline-terminated, case-insensitive, and all responses come back as JSON objects with an event field. This makes it easy to parse from any language on the host side.

Command Reference

Here’s the full set of commands the card understands:

HELLO - Device identification. Returns the unique device ID, firmware version, build timestamp, and git hash.

1 | → HELLO |

GET_STATE - Current tap statistics. Returns how many total taps have been recorded and how many unique links are stored.

1 | → GET_STATE |

DUMP [offset] [count] - Paginated link dump. Returns stored peer IDs with pagination support (default: offset=0, count=10).

1 | → DUMP 0 10 |

CLEAR - Reset all links and tap count. Preserves the device’s selfId and secret key. ACK is sent before the blocking EEPROM write to prevent serial timeout.

1 | → CLEAR |

PROVISION_KEY version key_hex - Provisions a 32-byte secret key for HMAC signing. This is used by NEXI to verify that tap data hasn’t been tampered with.

1 | → PROVISION_KEY 1 <64-char hex key> |

SIGN_STATE nonce_hex - Signs the current state with HMAC-SHA256 for server-side verification. The HMAC covers the device ID, nonce, tap count, link count, and all peer IDs.

1 | → SIGN_STATE <2-64 char hex nonce> |

The HMAC message is structured as: selfId (12 bytes) + nonce (N bytes) + totalTapCount (4 LE) + linkCount (2 LE) + [peerId × linkCount]. This ensures the server can verify the entire state is authentic and untampered.

All errors come back as JSON too, making them easy to handle programmatically:

1 | {"event":"error","msg":"unknown command: FOO"} |

Storage

The card needs to persist data across power cycles - it would be pretty useless if you lost all your tap connections when the battery dies at a concert. The STM32L0’s internal EEPROM emulation (backed by flash) is used for storage, with CRC32 integrity checking to guard against corruption.

1 | ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ |

Data Layout

The entire persistent image is 896 bytes, structured as PersistImageV1:

1 | Offset Size Field |

The magic bytes 0x424F4B41 spell out “BOKA” - a quick sanity check on load. The CRC32 is calculated using the STM32’s hardware CRC peripheral for speed, covering only the payload (not the header).

Each card can store up to 64 unique peer IDs. When the limit is reached, the buffer wraps around and overwrites the oldest links. The linkCount keeps incrementing past 64 to track total lifetime unique peers.

The Flash Write Problem

Here’s the thing about STM32L0 EEPROM emulation - it’s backed by flash memory with limited write cycles (~10,000 per page). A full 896-byte write takes 6-7 seconds and blocks the entire MCU. Each individual byte write can take 5-10ms. That’s a problem when you need to stay responsive for USB serial and TapLink communication.

Three solutions are implemented:

1. Delayed writes (2-second batch window) - Multiple changes within 2 seconds are batched into a single write. The loop() function checks a dirty flag and elapsed time before committing.

2. Optimized partial saves - Instead of writing 896 bytes every time:

saveTapCountOnly()writes just 8 bytes (tap count + CRC) - ~100x fastersaveLinkOnly()writes just 18 bytes (link count + new link entry + CRC) - ~50x faster

3. Chunked writes with yield - Full writes are broken into 32-byte chunks with 1ms delays between them, allowing serial interrupts to be processed:

1 | const size_t CHUNK_SIZE = 32; |

For the CLEAR and PROVISION_KEY USB commands, the ACK response is sent before the EEPROM write begins. This prevents the host from timing out while waiting for the blocking write to complete. Secret key writes (setSecretKey()) always save immediately with no delay - security-critical data shouldn’t sit in a dirty buffer.

Link Management

Before adding a new peer, hasLink() does an O(n) scan of existing links to prevent duplicates. When MAX_LINKS (64) is reached, the index wraps around:

1 | idx = idx % PersistPayloadV1::MAX_LINKS; // Circular buffer |

Oldest links get overwritten, but linkCount keeps going up so the total lifetime count is preserved for NEXI.

Initialization

On first boot (or after corruption), the storage initializes fresh:

- Try to load from NVM - validate magic, version, length, and CRC32

- If validation fails, zero-initialize everything, stamp the magic/version, copy the hardware UID into selfId, and write

- If selfId is all zeros (shouldn’t happen, but defensive), re-read from the hardware UID

Designing TapLink - A Masterless 1-Wire Protocol

The core challenge was figuring out how two cards communicate when they tap together. I designed TapLink - a device-to-device communication protocol over a single GPIO wire using an open-drain configuration. Neither card needs to be the “master.” Both cards are equal peers that negotiate who takes the lead.

Architecture

The protocol is layered cleanly so each concern is separated:

1 | ┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐ |

Electrical Interface - Open-Drain

The physical layer uses an open-drain configuration on a single GPIO pin. Both devices share one wire with internal pull-ups:

1 | Device A Device B |

- Idle state: HIGH (via internal pull-ups)

- Either device can pull the line LOW

- Wired-AND: the line is HIGH only if both devices release

- No bus contention is possible - this is key for safety

The GPIO switches between two modes:

| Mode | Config | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Release | INPUT_PULLUP | High-Z with pull-up (line goes HIGH) |

| Drive LOW | OUTPUT + LOW | Actively pulls line to ground |

Two Operation Modes

TapLink supports two modes - one for development and one for the real thing:

Eval Board Mode - USB-powered continuous monitoring for development on Nucleo boards. Sends periodic presence pulses and automatically negotiates on connection. This is what I used for all the prototyping.

Battery Mode - CR2032-powered with sleep/wake. The MCU sleeps until a tap wake-up interrupt fires, validates the connection is stable, then proceeds. Minimal power consumption for concert use.

Detection State Machine

When not connected, both devices send periodic presence pulses to announce themselves:

1 | Timing: |

When a device detects a peer’s pulse, the state machine kicks in:

1 | ┌──────────────┐ |

Role Negotiation - The Tricky Part

This is where the magic (and pain) happens. Both devices need to start bit exchange simultaneously, so they perform a synchronization handshake first:

- Release line, wait for HIGH

- Send 10ms sync pulse

- Wait for line HIGH

- Wait for peer’s sync pulse (up to 50ms)

- Wait for peer’s pulse to complete

- 5ms delay

- Send second 10ms sync pulse

- Wait for line HIGH

- 5ms final alignment delay

- Begin bit exchange

This achieves ~1-2ms synchronization accuracy between the two devices.

Then comes the UID bit exchange. The higher UID becomes Master. The first 32 bits of each device’s unique ID are compared, MSB first:

1 | Timing per bit: |

Why the 5ms drive period? The long drive period with mid-point sampling at 2.5ms ensures reliable reading even with ~2ms sync error between devices. Both devices are guaranteed to be in their drive phase when sampling occurs. This was one of the key insights that made the protocol work.

The Timing Nightmare

Here’s where things got painful. After getting USB serial working and implementing the 1-wire protocol, the master negotiation wasn’t working. The timing of the signals was off - two cards couldn’t reliably agree on who should be the master.

Here are all the timing constants that needed to be carefully tuned:

| Constant | Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| DEBOUNCE_TIME_US | 5,000 | Connection detection debounce |

| PRESENCE_PULSE_US | 2,000 | Presence pulse width |

| PULSE_INTERVAL_US | 50,000 | Time between presence pulses |

| BIT_DRIVE_US | 5,000 | Bit drive duration |

| BIT_SAMPLE_US | 2,500 | Sample point within bit slot |

| BIT_RECOVERY_US | 2,000 | Recovery between bits |

| SYNC_PULSE_US | 10,000 | Sync handshake pulse |

| SYNC_WAIT_US | 5,000 | Sync alignment delay |

| CMD_START_PULSE_US | 5,000 | Command start pulse |

| CMD_TURNAROUND_US | 2,000 | Send/receive turnaround |

| CMD_TIMEOUT_US | 100,000 | Command response timeout |

| SLAVE_IDLE_TIMEOUT_US | 2,000,000 | Slave disconnect timeout |

Debugging with AI and an Oscilloscope

After a lot of frustration, I turned to two allies: AI and an oscilloscope.

The first problem was link detection itself. My initial approach used a simple pulse to detect when two cards were tapped together - one device sends a pulse, the other detects it, and they move on to negotiation. Sounds straightforward, right?

In practice, the pulse-based detection was a mess. The timing wasn’t stable enough, and worse - the peer’s presence pulse could easily be mistaken as the start of actual data transmission. The two devices would get confused about whether they were still in the detection phase or had already moved into negotiation. The oscilloscope made this painfully obvious: pulses that should have been clean detection signals were getting mixed up with the beginning of the bit exchange.

With the oscilloscope confirming the problem, I turned to Grok and Opus for help restructuring the code. The key insight they helped me arrive at was to separate the detection logic entirely from the data exchange logic and introduce a proper state machine to manage the detection phase. Instead of one tangled flow where pulses could mean anything, each state (NoConnection, Detecting, Negotiating, Connected) had clear entry/exit conditions and its own pulse handling. This made it impossible for a presence pulse to be misinterpreted as a data signal - the state machine simply wouldn’t allow it.

Once I reworked the link detection logic with this state machine approach, things started clicking into place. Both devices could now reliably detect each other, sync up with a clean pulse, and enter the negotiation phase together.

Master Detection Working

With the detection fix in, master detection finally worked reliably. Two cards could now detect each other’s presence, sync up, and negotiate which one takes the lead using the UID bit exchange - all without confusion between detection and data phases.

Detection phase demo: illustrates 1-wire tap detection reliability with state machine design.Adding Command Exchange

With role negotiation working, adding the command protocol on top was straightforward. The packet format is simple:

1 | START pulse (5ms) → Turnaround (2ms) → Command byte → Turnaround (2ms) → Response byte |

Bit timing is the same as negotiation: 5ms drive, 2.5ms sample, 2ms recovery. Consistency here keeps things simple.

Commands and Responses

| Code | Command | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x01 | CHECK_READY | Master polls slave availability |

| 0x02 | REQUEST_ID | Master requests slave’s UID |

| 0x03 | SEND_ID | Master sends its UID to slave |

| Code | Response | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 0x06 | ACK | Command successful |

| 0x15 | NAK | Command rejected |

ID Exchange Sequence

Once roles are established, the actual ID exchange follows this flow:

1 | Master Slave |

Disconnect Detection

The protocol also handles disconnection gracefully from both sides:

- Master side: tracks consecutive command failures. After 3 failures, transition back to NoConnection. Invalid responses (0xFF from a floating line) count as failures.

- Slave side: tracks time since last command received. After 2 seconds of silence, transition back to NoConnection.

It Works! Exchanging IDs and Counting Connections

Finally - two cards can communicate, exchange their unique IDs, and count how many IDs they’ve collected!

What’s Next

The firmware works. Two Nucleo dev boards can detect each other, negotiate roles, exchange IDs, and store them - all over a single wire. But right now this is all happening on chunky development boards wired together on a desk. That’s not exactly something you’d bring to a concert.

The next step is turning this into an actual PCB. That means designing the schematic - taking the STM32L053R8 and all the supporting circuitry (USB connector, CR2450 battery holder, LEDs, the TapLink connector) and laying it all out properly. Then routing the PCB, getting it manufactured, and soldering up the first real Bokaka cards.

Stay tuned for part 3, where I’ll go through the full hardware design process - from schematic capture to holding a finished board in my hands.

Project is open source: diva-eng/BOKAKA